The Vilbil Blog

Digital-Native Art: Where Language, Culture, and Technology Converge

Throughout history, artists have seized upon the technologies of their age to transform how art is made and experienced. The invention of oil paint allowed Renaissance masters to achieve unprecedented depth and realism; photography challenged traditional notions of representation in the modern era; and video art opened up new dimensions of time and movement in the 20th century. Today, we enter another turning point: the era of digital-native art, works that exist entirely within digital spaces and are designed to be created, shared, and experienced through code, screens, and networks rather than as extensions of physical media.

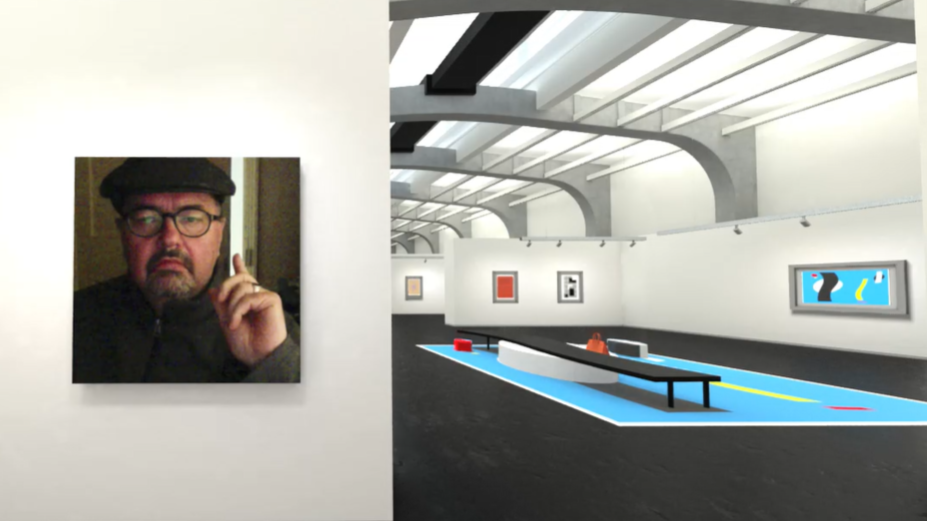

What sets digital-native art apart is more than its medium—it is a way of thinking. It values interactivity, immaterial form, and global reach. A leading figure in this field is British artist Robert Richardson, whose work moves fluidly between text and image, tradition and innovation.

Robert Richardson: From poetry to pixels

Richardson began his artistic career as a poet, concrete poet, and small press publisher before moving into text-based installations in the 1990s. By the 2000s, his focus shifted toward photography, resulting in several solo exhibitions, including at the Museum of Classical Archaeology, University of Cambridge, and the Museu Municipal in Faro, Portugal.

In 2014, Richardson returned to text art with digital realisations that gained international recognition, including a solo exhibition at the gallery of Eugen Gomringer in Germany. Since then, he has embraced digital media fully, producing abstract works and animations distributed both as limited-edition prints and as NFTs. His pieces have appeared in collections at the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and even on the bright screens of Times Square, New York.

Richardson’s ability to reimagine text — once static on the page — as a dynamic, screen-based experience exemplifies the digital-native turn: art that is not merely documented online, but created for and through digital space.

Why digital-native art matters

The rise of digital-native art highlights several broader cultural dynamics:

• Preservation and transformation of heritage. Digital tools allow artists to reinterpret language, literature, and cultural forms in ways that both preserve and reinvent them for new audiences.

• Expansion of access. Works displayed on global screens — from subway stations in São Paulo to Times Square — reach audiences traditional galleries cannot.

• New models of ownership. Through blockchain and NFTs, digital-native art redefines what it means to “own” an artwork, decoupling value from physicality.

• Interactivity as standard. Unlike static paintings, digital-native works often invite motion, manipulation, and participation, making audiences active co-creators of meaning.

This isn’t a niche trend. It is a cultural shift toward art that reflects the realities of a digital-first world.

The Vilbil and the digital-native horizon

For digital-native artists, traditional museums are often an imperfect fit. Their works lose something when reduced to documentation or simulation. What they need are spaces that can support their complexity, movement, and accessibility.

This is where projects like The Vilbil come in. As an online hub for art and artists, The Vilbil provides a natural environment for digital-native works — a place where visitors can engage interactively, without hardware barriers, and where artists can connect with global audiences on their own terms.

Robert Richardson’s journey shows how digital-native practices are already shaping this landscape. The challenge — and opportunity — for cultural institutions is to create platforms that honor these works in their native environment. The digital museum is not just a new container; it is a new cultural stage.

And in this space, digital-native art is not an outlier. It is the main event.

What sets digital-native art apart is more than its medium—it is a way of thinking. It values interactivity, immaterial form, and global reach. A leading figure in this field is British artist Robert Richardson, whose work moves fluidly between text and image, tradition and innovation.

Robert Richardson: From poetry to pixels

Richardson began his artistic career as a poet, concrete poet, and small press publisher before moving into text-based installations in the 1990s. By the 2000s, his focus shifted toward photography, resulting in several solo exhibitions, including at the Museum of Classical Archaeology, University of Cambridge, and the Museu Municipal in Faro, Portugal.

In 2014, Richardson returned to text art with digital realisations that gained international recognition, including a solo exhibition at the gallery of Eugen Gomringer in Germany. Since then, he has embraced digital media fully, producing abstract works and animations distributed both as limited-edition prints and as NFTs. His pieces have appeared in collections at the British Museum, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and even on the bright screens of Times Square, New York.

Richardson’s ability to reimagine text — once static on the page — as a dynamic, screen-based experience exemplifies the digital-native turn: art that is not merely documented online, but created for and through digital space.

Why digital-native art matters

The rise of digital-native art highlights several broader cultural dynamics:

• Preservation and transformation of heritage. Digital tools allow artists to reinterpret language, literature, and cultural forms in ways that both preserve and reinvent them for new audiences.

• Expansion of access. Works displayed on global screens — from subway stations in São Paulo to Times Square — reach audiences traditional galleries cannot.

• New models of ownership. Through blockchain and NFTs, digital-native art redefines what it means to “own” an artwork, decoupling value from physicality.

• Interactivity as standard. Unlike static paintings, digital-native works often invite motion, manipulation, and participation, making audiences active co-creators of meaning.

This isn’t a niche trend. It is a cultural shift toward art that reflects the realities of a digital-first world.

The Vilbil and the digital-native horizon

For digital-native artists, traditional museums are often an imperfect fit. Their works lose something when reduced to documentation or simulation. What they need are spaces that can support their complexity, movement, and accessibility.

This is where projects like The Vilbil come in. As an online hub for art and artists, The Vilbil provides a natural environment for digital-native works — a place where visitors can engage interactively, without hardware barriers, and where artists can connect with global audiences on their own terms.

Robert Richardson’s journey shows how digital-native practices are already shaping this landscape. The challenge — and opportunity — for cultural institutions is to create platforms that honor these works in their native environment. The digital museum is not just a new container; it is a new cultural stage.

And in this space, digital-native art is not an outlier. It is the main event.