BORIS CHETKOV

Display

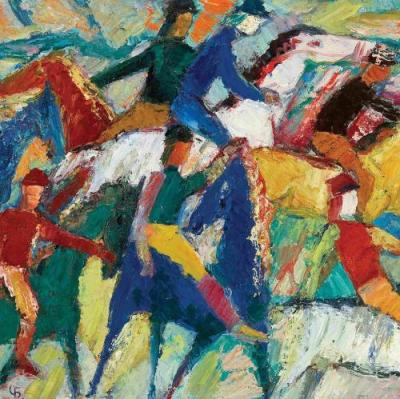

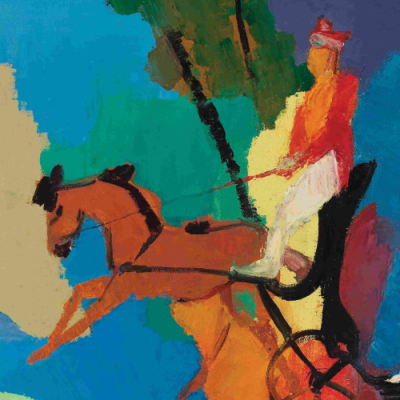

Boris Chetkov’s paintings are an exuberant affirmation of the power of personal vision in the face of ideological conformity. His style resists easy classification: it merges elements of Russian folk art, Primitivism, and spiritual abstraction with explosive, often euphoric use of color. Chetkov approached painting as a form of liberation—creative, emotional, and metaphysical. Unlike his Nonconformist contemporaries, who often engaged in overt political commentary, his rebellion was deeply internal. He did not mock ideology; he simply ignored it. His artistic language was neither Socialist Realism nor conceptual dissent—it was a personal, expressive universe built on light, rhythm, and color.

The influence of his glasswork is immediately visible: his paintings shimmer with a kind of internal radiance, as if lit from within. Layers of pigment are applied with painterly energy, sometimes bordering on abstraction, yet often returning to grounded forms—landscapes, flowers, horses, concerts, churches, and faces. Chetkov’s brushstrokes are muscular and gestural, with a tactile intensity that reflects his fascination with materiality. He did not aim for polished surfaces or academic draftsmanship; rather, his compositions are emotional scores, orchestrated like music in vibrant, contrasting harmonies. This musicality is especially evident in works like Concert or Theatre, where color replaces melody and rhythm is expressed in gesture.

Chetkov’s subjects are diverse, yet interconnected by recurring motifs: memory, folklore, spirituality, nature, and transformation. Ladoga Landscape and Staraya Ladoga Fog revisit childhood scenes through a dreamlike lens, turning provincial scenery into mystical realms. Works like Bacchanalia or Mating Call hint at mythic energies, fertility rituals, and primal forces, rendered through wild chromatic interplay. His still lifes—such as Still Life with Irises —abandon static realism in favor of expressive structure, breathing vitality into common objects. Even portraits, like Self Portrait in a Top Hat or African, are layered with theatricality, introspection, and symbolic exaggeration.

Chetkov’s formal experiments echo the early Russian avant-garde—Kandinsky’s spiritual abstraction, Goncharova’s primitivist elegance, Lentulov’s fractured color planes—but always filtered through his own intuitive method. There is no manifest or ideology behind his work. Instead, there is searching. His large canvases from the 1990s, such as Penguin Migration and Composition, push the boundaries of painterly freedom, exploding into fields of saturated light. These are not academic studies or ideological statements—they are acts of creative survival.

In the tightly controlled artistic landscape of the USSR, Chetkov’s independence cost him exposure, acceptance, and recognition. But the result is a body of work untouched by fashion, uncorrupted by conformity, and illuminated by an inner fire. His art is best understood not through movements or schools, but as a singular world—a visual diary of someone who created without compromise, following only the urgings of intuition, memory, and color.

Discover more about the artist featured here in the bio section: Boris Chetkov↗.

The influence of his glasswork is immediately visible: his paintings shimmer with a kind of internal radiance, as if lit from within. Layers of pigment are applied with painterly energy, sometimes bordering on abstraction, yet often returning to grounded forms—landscapes, flowers, horses, concerts, churches, and faces. Chetkov’s brushstrokes are muscular and gestural, with a tactile intensity that reflects his fascination with materiality. He did not aim for polished surfaces or academic draftsmanship; rather, his compositions are emotional scores, orchestrated like music in vibrant, contrasting harmonies. This musicality is especially evident in works like Concert or Theatre, where color replaces melody and rhythm is expressed in gesture.

Chetkov’s subjects are diverse, yet interconnected by recurring motifs: memory, folklore, spirituality, nature, and transformation. Ladoga Landscape and Staraya Ladoga Fog revisit childhood scenes through a dreamlike lens, turning provincial scenery into mystical realms. Works like Bacchanalia or Mating Call hint at mythic energies, fertility rituals, and primal forces, rendered through wild chromatic interplay. His still lifes—such as Still Life with Irises —abandon static realism in favor of expressive structure, breathing vitality into common objects. Even portraits, like Self Portrait in a Top Hat or African, are layered with theatricality, introspection, and symbolic exaggeration.

Chetkov’s formal experiments echo the early Russian avant-garde—Kandinsky’s spiritual abstraction, Goncharova’s primitivist elegance, Lentulov’s fractured color planes—but always filtered through his own intuitive method. There is no manifest or ideology behind his work. Instead, there is searching. His large canvases from the 1990s, such as Penguin Migration and Composition, push the boundaries of painterly freedom, exploding into fields of saturated light. These are not academic studies or ideological statements—they are acts of creative survival.

In the tightly controlled artistic landscape of the USSR, Chetkov’s independence cost him exposure, acceptance, and recognition. But the result is a body of work untouched by fashion, uncorrupted by conformity, and illuminated by an inner fire. His art is best understood not through movements or schools, but as a singular world—a visual diary of someone who created without compromise, following only the urgings of intuition, memory, and color.

Discover more about the artist featured here in the bio section: Boris Chetkov↗.